The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation team is shaping their next round of library innovation grants, and they’re looking for ideas. How might we help them support library evolution?

If you had a few million dollars to invest in libraries, how would you invest it? That’s exactly what the News Challenge team at the Knight Foundation is beginning to think about.

Last year the Knight Foundation ran a library grant initiative that pulled in hundreds of entries, an energetic discussion, and creative thinking from around the world. In 2016 they’ll do it again, and for starters, they’re inviting ideas on how to shape the challenge question participants will address.

There are so many ways to go with this. Since you asked, Knight friends, here’s what I’m thinking.

Given that (1) the foundation’s core mission is to “promote informed and engaged communities” and (2) libraries are built on community knowledge, I offer two related grant-shaping questions:

How might we leverage libraries as platforms for learning?

Libraries have long played a role in education: in all kinds of communities, librarians and library resources support formal education and enable personal development for people of all ages. That role has the potential to expand.

Once envisioned as the keepers and organizers of recorded knowledge, libraries today are helping create new knowledge in new ways. You can find libraries offering high school diplomas and trade certifications, creating and supporting MOOCs, and delivering courses in everything from U.S. citizenship and the English language to computer skills and financial literacy. Online and offline, libraries offer programs and resources that complement our schools, museums, and other elements of the community learning ecosystem. In a world where knowledge and skills are becoming obsolete more quickly, we need that ecosystem to be healthy and strong.

It’s no coincidence that new research from the Pew Internet Project establishes libraries as “opportunity hubs” for education, according to researcher John Horrigan, who presented preliminary findings at the American Library Association’s annual conference in June 2015.

How can libraries create or facilitate new and better opportunities for learning—in all its forms?

As a corollary, I would ask,

How might we help libraries share community knowledge?

Beyond the shelves and databases of codified knowledge, libraries are exploring ways to harness the knowledge of their own communities. That knowledge may be recorded but inaccessible for one reason or another, or it may be stored in the minds and experiences of local residents.

There’s great potential here, too, and we’ve just scratched the surface. “The community is the collection,” as David Lankes is fond of saying. Today library members are sharing their lives through human libraries, their expertise through TEDx talks, their personal stories through StoryCorps programs, their neighborhood smarts through LocalWiki collaborations. There are people who want to write things and make stuff and learn something, and other people who are willing to share what they have and teach what they know. And there are unconnected or inaccessible resources in local governments, nonprofits—even shareable private collections.

Libraries can be the connectors, the facilitators of knowledge sharing. How can we help a community tell its own stories? How can we tap into the expertise and experience of our neighbors? How can we create partnerships with organizations and agencies holding cultural, historical, or demographic information? How can we bring together those who want to know and those who have knowledge to share?

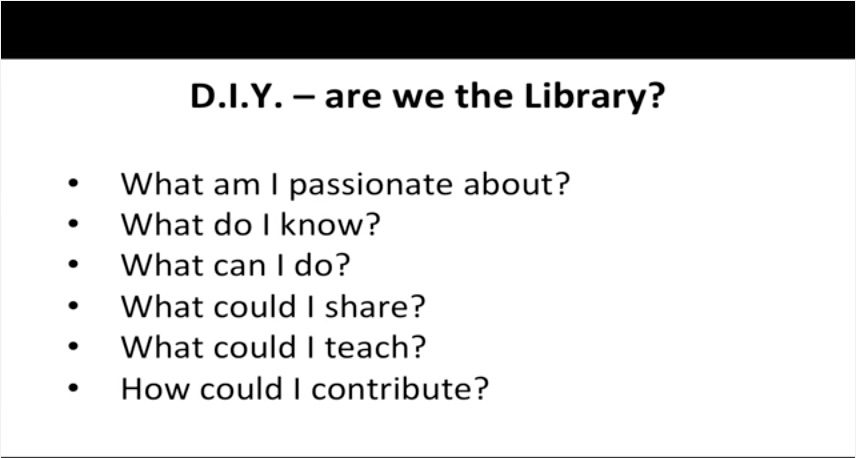

These are core principles of Common Libraries, where people aren’t just “patrons” or “users”; they’re participants who can ask:

Then there’s the question of real leverage

Whatever question the Knight Foundation seeks to answer, I think it’s worthwhile to consider not just the novelty of the responses but their potential for impact.

Local libraries are funded and managed independently, and that independence is both their greatest strength and greatest weakness. On our own we can better craft collections and services to meet the specific needs of a community, but it’s harder to leverage the resources and efforts of other libraries in other communities. As John Palfrey says in BiblioTECH, “We need radical collaboration in libraries, far beyond what happens today—not collaboration at the margins or collaboration as afterthought.”

Librarians are masters of sharing, and we need more ways to network our resources and spread our innovations.

So, in grants that are more than prototypes, I would favor proposals that encourage cooperative partnerships, help us build infrastructures, and make our national—and even international—library systems stronger as a whole. High-impact ideas will have the potential, ultimately, to reach broader audiences, support more than one library in one community, or be easily replicated (think open source code, shared documentation, and interoperable systems). We need proposals that will let other libraries take advantage of the good ideas without having to reinvent them.

How can we grow stronger together? Ω

Resources

The 2014 Knight News Challenge: Libraries website, including the program brief, hundreds of proposals, 22 winners, and a vibrant discussion.

Announcement of the 2016 Knight News Challenge: Libraries from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

Original illustration by Kerry Conboy.

Update: This post was republished by MediaShift as “How Can We Support Library Innovation?” on November 30, 2015.

Online and offline, libraries offer programs and resources that complement our schools, museums, and other elements of the community learning ecosystem.

Beyond the shelves and databases of codified knowledge, libraries are exploring ways to harness the knowledge of their own communities.

Comments are closed.