In study after study, libraries are ranked among the public’s most trusted sources of information. But how confident can we be in our position as trusted institutions—and how can we sustain that trust? Pew Research’s Lee Rainie helps us put the research into a broader context.

This is part one of a series. Part two is here.

We are proud of the data, study after study, that says libraries are among the most trusted institutions around. And proud we should be. According to a 2016 study by Pew Research, 78% of adults—about 8 out of 10 of your friends, neighbors, and colleagues—say that public libraries help them find information that is trustworthy and reliable. So say a whopping 87% of Millennials, ages 18 to 35, who are among the biggest library users in the United States.

We are proud of the data, study after study, that says libraries are among the most trusted institutions around. And proud we should be. According to a 2016 study by Pew Research, 78% of adults—about 8 out of 10 of your friends, neighbors, and colleagues—say that public libraries help them find information that is trustworthy and reliable. So say a whopping 87% of Millennials, ages 18 to 35, who are among the biggest library users in the United States.

While trust in many institutions has been declining for decades, libraries have held their ground. “We don’t have long-term readings on trust in librarians,” says Lee Rainie, director of Pew’s internet, society, and technology research. “If I had to guess, my sense is that it was high when these trust questions were asked about other institutions decades ago, so I’m not sure there has been any great change over time. But that’s a story in and of itself… Holding your own in an era where there is widespread decline of trust in other institutions is a helpful thing for libraries and librarians.”

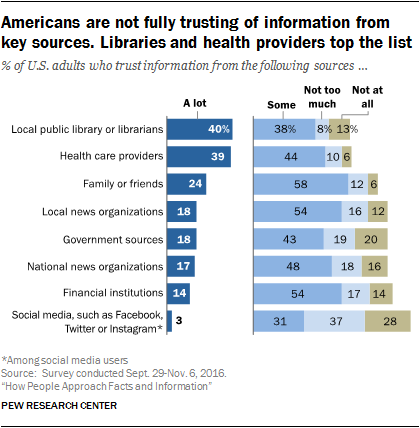

Even better than holding steady, we seem to be gaining ground. The number of adults who say they trust libraries “a lot” has risen significantly over the last two years, from 24% to 40%.* “One possible explanation is that this has been an era of increasing political polarization and that has impacted people’s levels of trust in institutions and each other,” suggests Rainie. “The debates over ‘fake news’ are the most dramatic examples of that. For some Americans it might be the case that in times of contention over truth and falsity there is a ‘flight to quality,’ and libraries have pretty high standings in those circumstances.”

It’s all good news, so far.

It’s complicated

But the whole question of trust… it’s complicated.

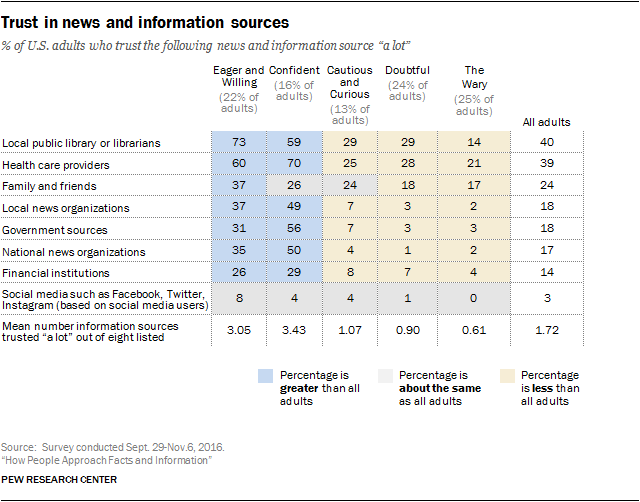

While confidence in libraries scores high with those who are relatively engaged with information and learning, there are those who are more cautious and much less trusting of the institutions around them. In an era of polarization and questionable news, perhaps it’s not surprising that Pew found one out of four American adults to be “information wary” when researchers looked at the different ways people approach facts and information. And only 14% of the wary folks said they trusted libraries a lot, even though more than a third had been to a library in the past year.

Look at it this way. If two couples have dinner together, one person at the table is likely to be wary, and there’s a very strong chance—an 86% chance—that the wary person does not have a lot of trust in libraries.

What does this all mean? When it comes to trust, it’s worth knowing our weak spots as well as celebrating our strengths. Libraries will never be everyone’s cup of tea. And public confidence is not something to get complacent about, especially when our environment is polluted with information that truly can’t be trusted and we, the librarians, are encouraging everyone to question their sources and think critically. Blind trust in anything is not a good idea these days, and every source has to prove itself worthy. We’re living “in the midst of persistent info-wars about news and information in public life,” points out Rainie. “These are challenging times for those who care about finding high-quality, reliable information.”

Established trust can also be compromised, weakened, lost, and sometimes it doesn’t take much for the ground to shift. Staying trustworthy takes conscious effort, and we’ll be in a better position to hold onto public confidence if we understand why people have granted us their trust in the first place.

Sources of trust

Why are libraries more trusted than so many other institutions? What is it that libraries are doing right? Well? Better? Differently? “We haven’t gotten into deep exploration of people’s trust in libraries and its sources,” says Rainie. “In focus groups and other encounters with library users, we hear that the nonpartisanship of libraries and librarians is a plus. They also talk about the abundance of information that is available at libraries. And they talk about the service ethic and basic disposition of librarians to be helpful without being heavy handed about how to navigate increasingly complicated information environments.”

“The other thing that is so fascinating in our data,” says Rainie, “is that people have watched libraries ‘reinvent themselves’ in the digital age and are pretty appreciative of that. A bunch of our studies highlight that affirmation.”

Journalist David Beard has also cited librarians’ mission of service—without a commercial motive—along with support for intellectual freedom and community engagement. “At a time when journalists are encouraged to engage with the community,” says Beard, “librarians have been doing that for years.“ Early experiences with libraries in childhood, he notes, also build positive associations with libraries that can last a lifetime.

Librarians like Dawn Finch have speculated that adherence to a professional code of ethics is a key factor, as it demonstrates a commitment to the public good that includes respect for diversity, equal opportunity, human rights, and individual privacy. “I firmly believe that the bedrock of this trust is the set of ethical principles around which we have built our careers,” says Finch, a trustee of the UK’s Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals. “The ethical principles set out by professional bodies like CILIP and the ALA are more than just a set of guidelines; they are a valuable public statement about who we are and what we do, and they protect both librarians and the people they serve.”

Trust is not something to take for granted, but something to hold dear, to protect and preserve. As Finch puts it, “this feeling of trust in our librarians is something to be nurtured and supported.” In part 2 of this story, we’ll look at some ways to do just that. Ω

Resources

How people approach facts and information, by John B. Horrigan for the Pew Research Center. September 11, 2017.

Libraries 2016, by John B. Horrigan for the Pew Research Center. September 9, 2016.

“Most Americans—especially Millennials—say libraries can help them find reliable, trustworthy information,” by Abigail Geiger for the Pew Research Center. August 30, 2017.

Illustration by Kerry Conboy.

* Pew Research’s Libraries 2016 report noted, ”There was a large increase in people saying libraries help ‘a lot’ in deciding what information they can trust from 2015, when the figure stood at 24%, to 2016, where it now stands at 37%.” In 2017, Pew’s How People Approach Facts and Information report put the number at 40%. Rainie notes that the questions were slightly different, asked in slightly different contexts, but it’s clear that there was a large increase between 2015 and 2017. ↩

“For some Americans it might be the case that in times of contention over truth and falsity there is a ‘flight to quality,’ and libraries have pretty high standings in those circumstances.”

—Lee Rainie, Pew Research

The whole question of trust… it’s complicated. Staying trustworthy takes conscious effort, and we’ll be in a better position to hold onto public confidence if we understand why people have granted us their trust in the first place.

Trust is not something to take for granted, but something to hold dear, to protect and preserve.