On library design, the evolution of library work, and how community connections are weaving their way into all that we do.

You could call them the library whisperers. Not because they speak softly in libraries, but because library buildings speak to them. Joyce Sternheim and Rob Bruijnzeels have learned a way of listening to libraries, of hearing the stories of their collections and their communities. It’s a skill they want to teach us.

You could call them the library whisperers. Not because they speak softly in libraries, but because library buildings speak to them. Joyce Sternheim and Rob Bruijnzeels have learned a way of listening to libraries, of hearing the stories of their collections and their communities. It’s a skill they want to teach us.

Bruijnzeels and Sternheim have spent years exploring how the design of public library buildings is influenced by the changing role of the library and the evolution of library work. Their new book, Imagination and Participation: Next Steps in Public Library Architecture, shares what they’ve learned through their experiences consulting on the design of award-winning libraries and experimenting with fresh ways of looking at libraries, the communities they inhabit, and the systems that support them (including library science education). The book features interviews with architects of library buildings, along with a methodology for librarians and architects to apply as they envision new buildings or reconceive old ones.

Longtime librarians, Sternheim and Bruijnzeels are part of the Ministry of Imagination, “a collective of creative thinkers and doers,” based in the Netherlands, “who jointly use their knowledge and imagination to help libraries and other cultural institutions make their future plans reality.” They also run Rogues, a nonprofit that organizes international study tours to learn about the visions and approaches of new public libraries.

Our conversation has been lightly edited for clarity. Full disclosure: I had an opportunity to review an early draft of the text for Imagination and Participation, but I have no financial stake in the project.

How did you become interested in library architecture?

Sternheim and Bruijnzeels: We’ve always had an interest in architecture, which was further sparked by the study trips to new libraries we organized. I guess Michel Melot, former director of the Center Pompidou Library in Paris, struck the right note when he said that every librarian is, up to a certain point, an architect, because he builds up his collection as an ensemble through which the reader must find a path.

But we also discovered that building a new library is pretty much the most creative phase in a librarian’s life. It’s a trigger to think about what you really stand for and how this should be reflected in the building. It’s the impetus to transform.

Why was it important to you to write this book?

All around the world we saw impressive new library buildings emerging, often designed by famous architects. We asked ourselves whether all these spectacular buildings really reflected a new vision of the role of the public library in society. We saw striking new buildings that, on closer inspection, had quite a traditional layout. The archetype of a library translated into ultramodern design. And then we also saw flashy buildings that offered space for a wide range of activities, but seemed to have lost their identity as a library.

We started wondering whether it was possible to design a building that is immediately recognizable as a library and at the same time gives shape to the new role of the library in society. So we embarked on an exploration into this new role of the library and, in particular, into the architecture that goes along with it.

We also discovered that there wasn’t a book yet that specifically deals with the architecture of public libraries. So all the more reason to write this book!

Some people see the role of the library building diminishing as we access more information online. What role do you see the physical building playing in the function of the public library and the life of a community?

If anything has become clear from the [COVID-19] lockdown, it is that physical meeting is essential for the well-being of people and of the community they live in. So the importance of the library as a public space, an open and accessible place where people from all sections of society are able to meet, cannot be emphasized enough.

But is has to be more than an inviting and attractive place to stay, with comfortable seating and study areas, good Wi-Fi and excellent coffee. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course, but it doesn’t automatically lead to an exchange of knowledge, ideas, and inspiration. And that is what we so badly need in today’s society. The fact that so much information is accessed online leads to a disturbing phenomenon: people increasingly become isolated within their own bubble of like-minded people, excluding themselves from opportunities to encounter different views and ideas. It leads to increasing inequality and polarization, and a declining sense of community. Complex issues that require a next step in the development of the public library. This next step concerns the redesign of processes aimed at stimulating and supporting active citizenship and participation. Processes that require a different layout of space, and thus a different architecture: a library building that stimulates curiosity, reflection, and conversation.

So as society changes, the work of librarians changes, and our concept of a library building must change as well. Tell me more about that. How does social change influence the way we think about library spaces?

In the past, library space was primarily defined by the number of bookcases and how they were arranged. Now we literally need to make way for new processes to engage people in face-to-face conversations, involve them in problems and topics that affect their lives and their local communities, and stimulate them to jointly come up with smart and creative solutions.

We need “the creative intelligence of communities,” or the “Scenius” as it is called by musician and producer Brian Eno. He introduced this term to counter the idea that innovation in art and culture comes from geniuses working in solitude, when in reality great ideas are often spawned by a group of creative individuals. For him, it simply confirms that good work does not come in a vacuum, and that creativity is always, in a sense, a collaboration, the result of a mind connected to other minds.

It’s a fundamental reform that goes beyond creating a welcoming space that is accessible to everyone. In order to stimulate participation and citizenship, the library must actively challenge people to join discussions, add their own knowledge and experience, and come up with new ideas that become part of the collection and are shared within the community. This calls for a library that triggers curiosity and encourages reflection—an environment that is thought provoking and sometimes even a bit disruptive, with a prominent role for the collection.

It’s an interesting combination of static and dynamic. When we invest in a physical building, we expect the structure to stand for a long time—but we also expect communities and library work to keep evolving. How do we create libraries that will adapt to change?

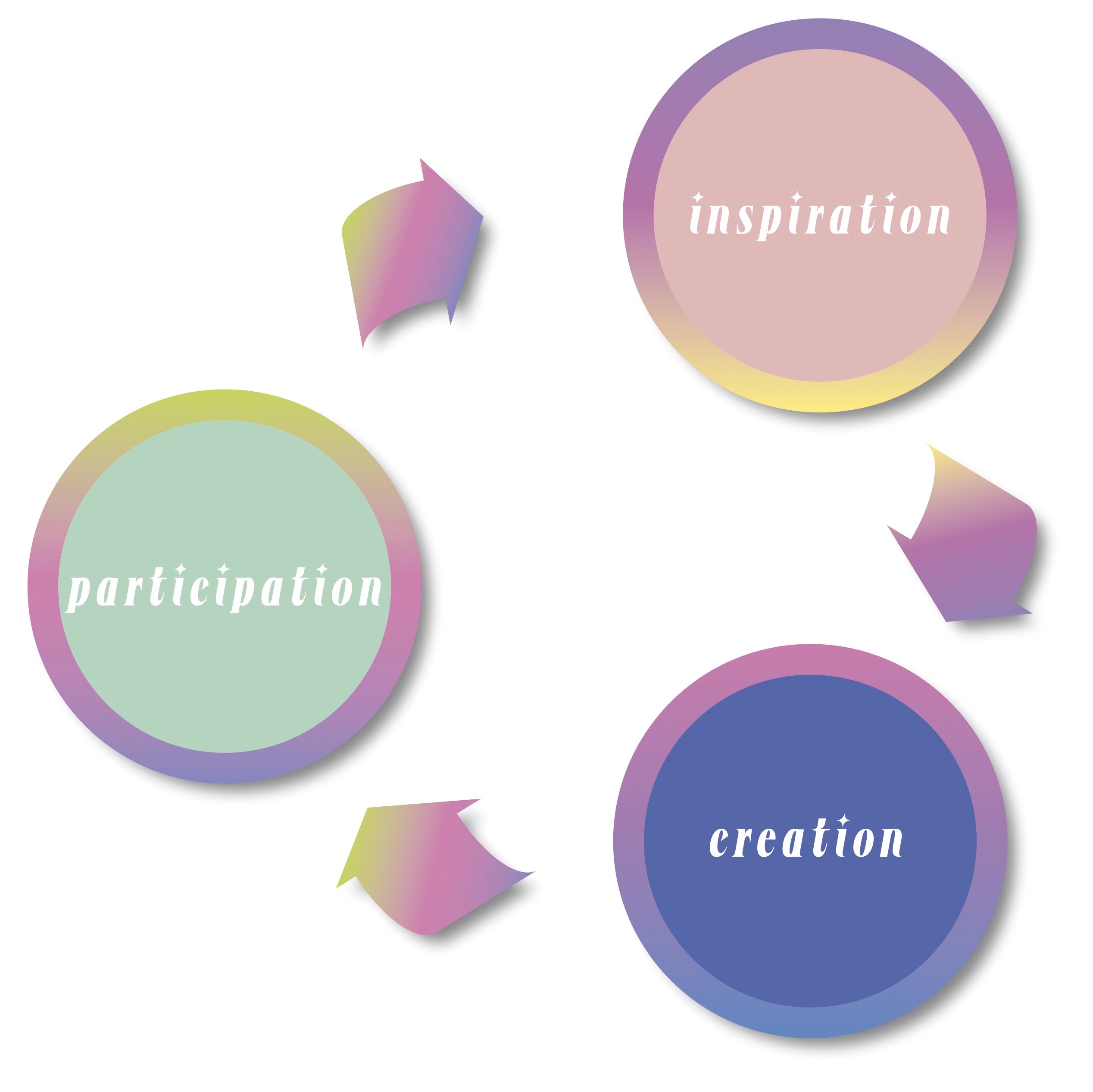

Well, it can certainly not be solved by introducing bookcases on wheels! In general, architects and designers are very capable of coming up with creative solutions for this problem. An example is the LocHal in Tilburg [the Netherlands], where designer Petra Blaisse introduced huge curtains to screen off space or to open it. But above all, flexibility must be found in the programming, in the application of the new work process of inspiration, creation, participation, that we describe. The continuously changing programming that results from this process leads to a different layout of space and a varied use of the makerspaces.

LocHal Public Library in Tilburg, the Netherlands. CIVIC Architects.

You put a lot of emphasis on each library having a unique identity in the local community. How do you find the essence, the uniqueness, of a particular library?

It’s important to investigate the DNA of the city and the community. What is the history, how can we describe the city’s character? But also: what do the residents and the city need? If you want to stimulate the Scenius, the creative intelligence of the community, you need to know how that community works and what the needs and issues are.

If the project concerns an existing building, it could be interesting to take the history of that building and/or its original purpose as the basis for your narrative. And finally, it is also about what you, as a library, want to be good at. Your mission, your motivations, etc. All of this together determines the library’s narrative.

To illustrate how different urban contexts can lead to very different libraries, the book contains a case study of Forum Groningen and LocHal Tilburg, two award-winning libraries in the Netherlands, that were both completed in the same year, but couldn’t be more different. Yet, both buildings perfectly reflect the character of the two cities. In the Forum, elegant, urban Groningen [below] has gained a stylish element of vertical city center, while the soul of raw, “maker city” Tilburg comes into its own in the industrial character of the LocHal [above].

The Forum in Groningen, the Netherlands. NL Architects.

When librarians and architects work together, it may be a new experience for both. What are some things librarians and architects can do to build good working relationships?

Instead of the traditional relationship between client and contractor, they should think of each other as partners. At the very beginning of the design process they should be open to each other’s ideas, reflect upon them and discover different perspectives, to ultimately arrive at a shared vision. They may also disrupt each other a bit by coming up with something that is not so obvious.

For instance, the indoor garden we created in the library of Schiedam, the Netherlands. The public library moved into a building from the 18th century with a rectangular courtyard and a surrounding gallery. It strongly reminded us of a cloister, and since most cloisters have gardens, this soon led to the idea of creating a splendid green space for the people of Schiedam. An indoor garden where they could read, relax, enjoy conversations, and “grow their brains.”

Schiedam Library, renovated 18th-century Korenbeurs building, the Netherlands. Hanratharchitect.

Many of the examples in the book involve Dutch architects and libraries. Do you see international differences in the process of public library design, or are the lessons here universal? Could librarians in other environments, like academic libraries, learn something from your thought process as well?

We think the lessons are universally applicable, because the starting point for the design of the library is the new work process of inspiration, creation, and participation. It is even conceivable that this process can also be used for academic libraries and museum libraries. After all, they also benefit from the exchange of knowledge and ideas.

Did your own thinking evolve in the process of writing this book? What did you learn?

We have found that architects have great ideas about what a library should be.

We talked to Jo Coenen, for instance, an internationally renowned Dutch architect with an extensive oeuvre, which includes the Amsterdam Public Library. When we asked him what constitutes a library, he emphasized the importance of gathering knowledge, and sharing it in order to be able to interpret current events. And to achieve this, the collection is of the utmost importance. A library building should celebrate its collection, he said.

We were also impressed by a comment from Rick ten Doeschate of CIVIC, the architects of the LocHal. He said: “The library is partly based on the principle that you don’t just come there to consume knowledge, but perhaps also to bring something yourself. That places different demands on such a space.”

It proves that what Michel Melot said about librarians also goes for architects, but then the other way around: to a certain extent they are librarians! Ω

Resources

The Imagination and Participation website provides sources, references, and links to websites and other materials that supplement the book Imagination and Participation: Next Steps in Public Library Architecture.

The LocHal: From Train Depot to Cultural Citylab tells how an expansive industrial building in the heart of Tilburg’s railway zone was transformed into a bustling library and community gathering space.

The Chocolate Factory in Gouda is another Dutch library that draws on the history of the building: a former production house for chocolates now generates knowledge and ideas as a collective of the public library, the local archives, a printing society, and a restaurant—partners undivided by walls, who share spaces and ideas and activities. Chocolate Factory, Hanratharchitect.

The new Groningen Forum is an urban cultural center that incorporates the public library, exhibitions, a cinema, a museum of comics and games, a children’s Wonderland, makerspaces, and more. Library collections are integrated into the different themed areas. Here’s a look at the building, bottom to top.

For librarians, “building a new library is… a trigger to think about what you really stand for and how this should be reflected in the building. It’s the impetus to transform.”

—Joyce Sternheim and Rob Bruijnzeels

“The importance of the library as a public space, an open and accessible place where people from all sections of society are able to meet, cannot be emphasized enough.”

—Bruijnzeels and Sternheim

“In the past, library space was primarily defined by the number of bookcases and how they were arranged.

“Now we literally need to make way for new processes to engage people in face-to-face conversations, involve them in problems and topics that affect their lives and their local communities, and stimulate them to jointly come up with smart and creative solutions.”

—Sternheim and Bruijnzeels

How do we create libraries that will adapt to change?

“Above all, flexibility must be found in the programming.”

—Bruijnzeels and Sternheim

“The library is partly based on the principle that you don’t just come there to consume knowledge, but perhaps also to bring something yourself. That places different demands on such a space.”

—Architect Rick ten Doeschate

Comments are closed.